Japan has long been known for its cleanliness, order, and quiet respect for others—values that stem from a way of life deeply rooted in Shinto traditions. In the past, Japan’s tourist destinations were also tranquil places, where one could enjoy the beauty and flavors of the four seasons, regardless of where they went.

However, in recent years, this harmony has begun to crumble due to overtourism and illegal stays caused by many foreign travelers and residents. Many Japanese people do not wish to welcome foreigners who behave in such ways. While it may not be easy for foreigners to understand the “unspoken rules” that help maintain harmony among the Japanese, we hope they will follow the old saying, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” and act in a way that respects Japanese customs while in Japan.

This article offers practical advice and cultural insights to help foreigners live more comfortably—and be truly accepted—within Japanese society.

Those who wish to enjoy travel or daily life in Japan will find that by understanding not only what to do, but also why Japanese people value certain behaviors, they can build deeper relationships and live a peaceful, pleasant life in Japan.

【contents】

1. A Clean and Quiet Country: Japan

1-1. The Serious-Minded Japanese

A Breathtaking View of Mt. Fuji and the Tea Fields, Shizuoka Pref. Source: JR Tokai Tours

Japan is blessed with four distinct seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter. In spring, colorful flowers and fresh green leaves brighten the landscape, while in autumn, people delight in the beauty of the changing leaves. Each season offers scenes that please both the heart and the eyes.

Thanks to these clearly defined seasons, there are vegetables and seafood that can only be enjoyed at certain times of the year. To savor them together with sake—Japan’s national beverage, brewed in ways possible only in this country—is truly a priceless experience.

Japanese cuisine is not only delicious; every dish is artfully arranged with great attention to presentation. When foreign visitors encounter such dishes for the first time, they often hesitate to use their chopsticks, saying, “This is art.”

Cities and villages throughout Japan are exceptionally clean, with not a single piece of litter on the streets. Unlike in many other countries, graffiti on walls is extremely rare. Both the interiors and exteriors of homes are designed not just for practicality but also with the intricate craftsmanship found in Japanese handwork. The lighting is not merely bright; it skillfully balances light and shadow, creating a sense of calm and comfort in every room.

People place the highest value on mutual respect, believing that wa—harmony—is the foundation of a prosperous society. Unlike Westerners, who often emphasize self-assertion, the Japanese make decisions while respecting the feelings and thoughts of others.

1-2. Harmony Among People

Japan does not have a clearly defined religion like those in the West. Since ancient times, Shinto has existed as a fundamental spiritual framework for Japanese life.

Kyoto, Sanzen-in — Source: JR Tokai Tours

By the mid-6th century, Buddhism, one of the world’s major religions, was introduced to Japan. In Europe, the arrival of a new religion often led to the exclusion of existing faiths and even to “religious wars,” but in Japan, Shinto and Buddhism have coexisted peacefully from that time until today.

This reflects the Japanese capacity for spiritual tolerance. Traditional Japanese culture has long embraced the principle of “Harmony is to be valued” (from Prince Shōtoku-taishi’s Seventeen-Article Constitution), which emphasizes blending differing elements into a harmonious whole.

Prince Shōtoku-taishi was featured on the 1,000-yen banknote from January 7, 1950, to January 4, 1965.

Japanese people, as described above, value harmony and mutual promises with their neighbors and dislike conflict. Unlike many other countries, Japan has no history of institutionalized slavery, and Japanese society is characterized by a noble regard for treating others as human beings.

On the other hand, strict notions of privacy are weak. In rural areas, people often leave their front doors unlocked at night. In traditional Japanese-style houses, it is not customary to lock the doors of individual rooms; the doors often have no locks at all.

Historically, Japanese people have lived trusting even strangers. However, it is deeply regrettable that in recent years, with the increased presence of foreign residents in Japan, various crimes have risen.

In Japan, the two religions of ancient Shinto and Buddhism, introduced in the 6th century, coexist, and Japanese people incorporate both into their daily lives. However, unlike other religions around the world, there is no daily worship or weekly church service. People visit Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples as needed.

1-3. Sumo as a Sacred Ritual

Sumo is extremely popular, not only among Japanese people but also among foreigners.

Although sumo may appear to be a sport, at its core it is a sacred ritual. It is a ceremonial event in which people pray to the gods for abundant harvests and the health of their families.

Sumo is a divine ritual. When a wrestler reaches the rank of yokozuna (grand champion), he visits the Nomi no Sukune Shrine in Sumida, Tokyo, which enshrines the god of sumo, to report his achievement.

Before and after matches, wrestlers show respect to their opponents, whether they win or lose. Before a match, they perform shiko (stomping exercises) to honor the gods. They scatter salt on the dohyō (sumo ring) to purify the ring and to pray not to get hurt. When receiving prize money after a victory, wrestlers pay respect to the three gods associated with sumo.

At the conclusion of a tournament, a ceremony called yumitori-shiki is performed to purify the dohyō on behalf of the winner of the final match.

All of these rituals are intended to pray for the health of those involved and for bountiful crops. Sumo carries this profound spiritual significance.

2. Nuisance Behavior by Foreign Residents

In recent years, foreigners have begun to reside in or visit Japan, and this has made it increasingly difficult to maintain the quiet, clean, and considerate social environment that Japanese people have cultivated over many years.

Japanese people have no objection to foreigners living in Japan, but they do not want the peaceful society—built on the traditional harmony between people—to be disrupted.

Recently, the following nuisance behaviors by foreign residents in Japan have become apparent, causing discomfort and concern among Japanese citizens:

- Illegal stay by refugees

- Abuse of refugee application procedures to unlawfully extend residence

- Defiance after deportation orders

- Espionage activities

- Improper land acquisition

- Investment purchases of high-rise apartments without actual residence

- Failure to register as residents

- Non-payment of resident taxes

- Conversion of apartments for short-term rentals, displacing Japanese residents

- Noise disturbances at night

- Violations of garbage disposal rules

- Noise, vibration, and smoke from demolition or construction sites

- Free-riding on health insurance, medical care, and high-cost medical treatment

- Fraudulent automobile license renewals

- Non-enrollment in mandatory car insurance

- Frequent criminal activity

- Sexual offenses

- Illegal handling of drugs

- Theft (wires, vegetables, fruits)

- Burglary

- Acts of violence

- Intimidating behavior toward Japanese citizens

3. Troublesome Behavior by Foreign Tourists

Foreign tourists who stay in Japan for a short period often do not fully understand the Japanese personality or way of life. As a result, they cause various kinds of trouble for Japanese people, as shown below.

- Carrying large luggage (on buses, trains, at tourist sites, etc.)

- Speaking in loud voices

- Walking in large, disorderly groups at sightseeing spots

- Taking hotel property, such as TVs, paintings, or small items (theft)

- Improper toilet use (in hotels and public facilities)

- Improper climbing of Mt. Fuji (inadequate clothing, “bullet climbing,” no lodging reservations, etc.)

- Breaking rules

- Not lining up

- Not waiting one’s turn

- Occupying priority seats on trains or buses

- Taking photos where photography is prohibited

- Disturbing behavior in museums (loud talking, photography)

- Taking photos of Mt. Fuji or other sights from the middle of the road

- Entering private property without permission to take photos of Mt. Fuji, etc.

- Abandoning unwanted suitcases at hotels and other places

- Lack of cleanliness (improper use of public facilities)

- Eating while walking

- Littering food waste

- Medical expenses: reluctance to pay or no travel insurance

- Medical costs for foreigners should be charged at a triple rate

Comments on the medical charge from Chinese netizens:

“That’s reasonable. (By charging higher fees,) Medical resources paid for by people who pay insurance in Japan will not be taken away. Otherwise, many Chinese tourists would come for short stays and visit hospitals.”

“My father was once hospitalized in Japan without insurance, and it cost more than 1.3 million yen in four days. But I think that’s necessary. Otherwise, more short-term visitors would come to Japan for medical treatment, placing even more strain on Japan’s already limited medical resources.”

3-1. Why It Causes Trouble

As explained earlier, Japanese people enjoy spending time quietly with others, surrounded by beautiful seasonal scenery and a clean environment. They prefer to savor meals peacefully and have a pleasant, calm dining experience.

To maintain this atmosphere, they avoid littering, speaking loudly, or laughing boisterously, so that everyone can equally enjoy the moment. This stems from a deep sense of respect for others. When speaking, one’s voice only needs to be loud enough for the person in front to hear—there is no need for someone five meters away to catch the conversation.

The behaviors listed in Sections 2 and 3 can easily make nearby Japanese people uncomfortable or even place them in danger. Foreigners often say that they have the freedom to do or say whatever they want. Japanese people think the same way, but the difference is that Japanese people are always mindful not to inconvenience, harm, or make others feel unpleasant.

Foreign residents who wish to live in Japan, as well as tourists visiting Japan, are strongly encouraged to be fully aware of this point.

4. Japanese Personality

4-1. Japanese Customs, Buddhism, and Zen in Daily Life

Whether visiting Japan or planning to live here, it helps to understand the Japanese way of life, including their customs, habits, and social etiquette. As the saying goes, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

Shinto: Harmony with Nature

Shinto ceremony. Source: GOOD LUCK TRIP

Shinto wedding.

Shinto, Japan’s indigenous spiritual tradition, emphasizes respect for nature and ancestors. It teaches that gods inhabit natural objects like mountains, rivers, trees, and fire. Shinto is inclusive and non-dogmatic, allowing it to coexist peacefully with Buddhism or Christianity.

Shrines are everywhere in Japan, and people visit them to pray or make wishes. Shinto also shapes daily life and ceremonies, including weddings and seasonal festivals, encouraging respect, cleanliness, and harmony in everyday life.

Buddhism: Life, Death, and Mindfulness

Buddhism quietly influences daily life in Japan. Funerals and memorial services are mostly Buddhist, while joyful events such as births are often Shinto. Buddhist teachings, especially impermanence (mujo), encourage people not to cling to possessions and to value the present moment.

Daibutsu @ Todaiji-temple, Nara Pref.

Zen, a branch of Buddhism, has shaped Japanese simplicity, quiet reflection, and mindfulness. It influences cultural practices such as tea ceremonies, flower arrangement (ikebana), Japanese gardens, and vegetarian temple cuisine (shojin ryori). Even saying itadakimasu before meals expresses gratitude for life, a reflection of Buddhist values.

During zazen (seated meditation), if you feel drowsy or your concentration starts to wander, a monk may gently strike your shoulder with a kyosaku (encouragement stick). This helps you regain focus and deepen your mental discipline.

Zen: Simplicity, Focus, and Everyday Mindfulness

Zen Buddhism, introduced from China, emphasizes self-awareness, meditation (zazen), and mindful attention to daily activities like cleaning or cooking (samu). Its principles extend to aesthetics and lifestyle: simplicity (wabi), appreciation of natural imperfection (sabi), and living fully in the present.

Examples of Zen in everyday Japanese life:

- Cleaning and organizing as a spiritual practice

Children clean schools, and employees tidy workplaces. While in many Western countries cleaning is “someone else’s job,” in Japan it is seen as a way to cultivate mindfulness and respect. - Caring for things and valuing longevity

Broken items are repaired and reused rather than discarded. This reflects wabi-sabi, finding beauty in imperfection. Specialized workshops even restore toys and household items. - Appreciating silence and stillness

Japanese people value quiet in gardens, tea rooms, and hot springs. In Zen, silence mirrors the mind, whereas in Western culture, silence is often uncomfortable. - Graceful and efficient movements

Tea ceremonies, cooking, or the work of clerks and train staff demonstrate careful, waste-free movements. Each action reflects focus, mindfulness, and wholehearted engagement. - Savoring the present moment

Seasonal changes and seasonal foods are carefully appreciated. Zen teaches living fully in the present, so Japanese people enjoy the current season’s scenery, wind, and harvests from land and sea.

Even if Japanese people do not consciously practice Zen, it naturally permeates their daily lives. From cleaning habits to social etiquette, from aesthetics to seasonal awareness, Zen is quietly integrated into everyday routines, making ordinary life feel peaceful, mindful, and harmonious.

4-2. Avoiding Conflict

Japanese people generally dislike disputes, reflecting the cultural value of wa — harmony.

Prince Shōtoku, who served under Emperor Suiko (593–628), wrote Japan’s first constitution, the Seventeen-Article Constitution. Its opening line states: “Harmony is to be valued.”

Historically, living on an island made cooperation essential, so Japanese culture developed a preference for compromise and indirect communication rather than confrontation.

Today, this continues in everyday life. Japanese people often use subtle, indirect expressions and pay attention to others’ feelings, avoiding open conflict. Maintaining harmony is seen as a virtue.

4-3 Background of Modest Self-Assertion

The reason Japanese people are often said to have “weak self-assertion” stems from a combination of cultural, linguistic, and social factors.

In my experience, Japanese people often share only the key points in meetings or conversations, while many thoughts remain in their minds. In contrast, foreigners tend to speak quickly and at length, leaving little or nothing in their minds afterward.

Cultural Factors

- A deep respect for harmony (wa) and a tendency to avoid conflict.

- Confucian-inspired hierarchical and group-oriented values encourage individuals to avoid standing out and to prioritize group harmony.

Linguistic Factors

- Frequent use of ambiguous expressions such as “maybe” or “I’ll think about it” makes it harder to express strong opinions.

- A culture of reading the atmosphere means people often communicate through nuance rather than explicit words, which can appear as weak self-assertion to foreigners.

Social Factors

- Japan’s history as an island nation with few external threats fostered a culture emphasizing internal harmony.

- Education emphasizes cooperation, with relatively little training in debate or assertiveness compared to Western countries.

Impact on International Business and Diplomacy

- Japanese people may appear too willing to make concessions and leave others uncertain about their true thoughts.

- Ambiguous expressions and silence, common in Japanese communication, can sometimes lead to distrust abroad.

Conclusion

Japanese modest self-assertion is not a “weakness” but a sophisticated social skill aimed at preserving relationships. However, in international contexts, this approach is not always understood and is often perceived as insufficient self-assertion.

4-4. Bowing

Japanese people bow to each other many times, whether they are standing and talking or sitting and having a conversation. This act is called ojigi (bowing).

Japanese people greet others frequently.

4-4-1. Expression of Respect and Humility

Bowing during conversation is a sign that says, “I respect you.”

It is a natural way to show respect by lowering one’s head at appropriate moments—such as at pauses in the conversation or in response to what the other person says.

Especially when expressing apology, gratitude, or agreement, Japanese people accompany their words with physical gestures that reflect their feelings.

4-4-2. A Gesture of Trust and Reassurance

Bowing is also a way to show that one has no hostile intent.

Even in casual situations like chatting while standing, people unconsciously bow to narrow the emotional distance between themselves and others.

4-4-3. A Habit Engrained in the Body

In Japan, children are taught the concept of rei (courtesy or respect) from an early age at home and in school.

From a young age, they learn to give a small bow—called eshaku—whenever they meet someone.

Since bowing accompanies almost every situation—starting and ending a class, greeting, apologizing, or expressing thanks—it becomes second nature.

This is why some people even bow while talking on the phone or sending an email, without realizing it.

4-4-4. Regulating the Rhythm of Conversation

Bowing also serves to create pauses and rhythm in conversation.

By slightly lowering the head to acknowledge what the other person has said, to move to the next topic, or to compose one’s thoughts, the flow of the conversation becomes smoother and more harmonious.

4-5. “Hai, Hai”

When Japanese people are having a conversation or talking on the phone, they often say “hai, hai.”

While “hai, hai” literally corresponds to the English “yes, yes,” it does not necessarily mean that the listener agrees with what the speaker is saying.

I generated an image with AI to illustrate this.

In English, this type of response is known as a “short response” or “listening reaction.”

Linguistically, it is called a “backchannel.”

Therefore, “hai, hai” means “I understand what you are saying,” rather than “I agree with you.”

Even while saying “hai, hai,” the listener may actually think, “I understand what you’re saying, but I don’t agree,” or even “I disagree with your opinion.”

5. The Japanese Love of Cleanliness

5-1. Taking Your Trash Home

“In Japan, there’s no trash on the streets. I can’t believe it!”

From the perspective of foreign visitors, Japanese cities, towns, villages, roads, public spaces, trains, and even the Shinkansen are remarkably clean. Visitors often ask why this is so.

For Japanese people, however, this is completely normal.

Indeed, reflecting on my own experiences walking through foreign cities, trash is scattered everywhere. In contrast, very little trash is found on Japanese streets.

Until about 30 years ago, trash bins were available on streets, at train stations, and in large commercial facilities. However, at that time, there were a series of bombing incidents targeting trash bins in public spaces by left-wing activists, and as a result, the bins were removed.

After that, when people generated trash while outside, they began to carry it home or back to their workplace to dispose of it properly. This is considered completely normal in Japan. Foreign visitors should also carry a bag for their trash when walking around Japanese cities.

From an early age, Japanese children are taught at school how not to produce unnecessary trash. Wrappers from snacks, gum, or cigarettes are taken home or back to hotels to be disposed of.

In Japan, residents often volunteer to collect trash in their neighborhoods.

Source: Toda City, Saitama Prefecture

5-2. Washlet

“The toilets in Japanese hotels are amazing. Are they like this in ordinary homes too?”

A bidet toilet in Japan.

Typical home birth room.

The bidet toilet seat with warm water cleansing—commonly known as a Washlet—was first released in Japan in 1980. Initially, it simply sprayed warm water for cleaning when a button was pressed.

Today, the household adoption rate across Japan is 80.3% (as of 2021). They are installed in offices in cities, hotels, and large commercial facilities nationwide. Some models automatically lift the toilet lid when a person approaches. Users can adjust the water temperature and pressure, and warm air drying is also available.

After use, the toilet automatically flushes, and the lid closes by itself. To mask sounds during use, some models can play water stream noises or music according to preference. They are also equipped with devices that absorb and eliminate odors.

In addition, deodorant sprays are often used after use. Japanese people have developed a habit of always considering others, ensuring that they do not cause inconvenience to the next person. At drugstores, you can find a wide variety of toilet deodorizers and air fresheners with different floral scents.

In the past, TV commercials for Washlets went like this: red paint was put on the back of a hand. Which method cleans it better—wiping with dry tissue or washing with warm water? The answer was obvious.

5-3. How Foreigners Saw the Japanese in the Late Edo Period

Foreign visitors to Japan during the late Edo period noted that the Japanese were a very clean people. Even during the Samurai era, when men wore chonmage topknots, they maintained a hygienic lifestyle.

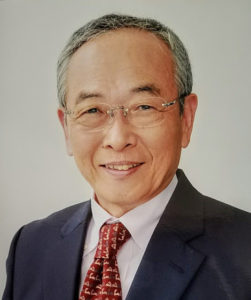

Sir Rutherford Alcock, British Envoy (arrived 1859)

“Generally speaking, the Japanese are a clean people who frequently wash their bodies without fear of being seen. They wear very little clothing and live in well-ventilated houses. Their homes are spacious and face streets that are also well-ventilated, and no one is allowed to place anything unpleasant or heavy on those streets. In terms of cleanliness, the Japanese surpass other East Asian peoples, particularly the Chinese.”

Edouard Suenson, Danish Naval Officer (arrived 1866)

“The Japanese love of cleanliness far exceeds that of the Dutch. This applies not only to their homes but to people themselves. They cannot consider their day complete without going to public baths after work. There, they spend hours bathing, washing their underwear, and chatting.”

Heinrich Schliemann, German Archaeologist (arrived 1865)

“There is no doubt that the Japanese are the cleanest people in the world. Even the poorest individuals go to public baths located throughout towns at least once a day. Japanese people find foreign customs extremely unhygienic—for example, blowing one’s nose with a handkerchief. They use paper tissues instead.”

Suenson also wrote, “Westerners carry dirty handkerchiefs in their pockets all day, which the Japanese simply cannot understand.”

Schliemann wrote similarly, noting that Japanese people are horrified when foreigners use the same handkerchief for several days.

Townsend Harris, U.S. Consul (arrived 1856)

Harris established the U.S. Consulate in Kakizaki, Shimoda, Shizuoka Prefecture. He noted that even the poor villagers were clean. Unlike poor villages elsewhere in the world, there was no trace of typical filth. Their homes were maintained with as much cleanliness as necessary.

The first U.S. Consulate in Japan, established at Gyokusen-ji in Shimoda, Kakizaki. Source: Shimoda City.

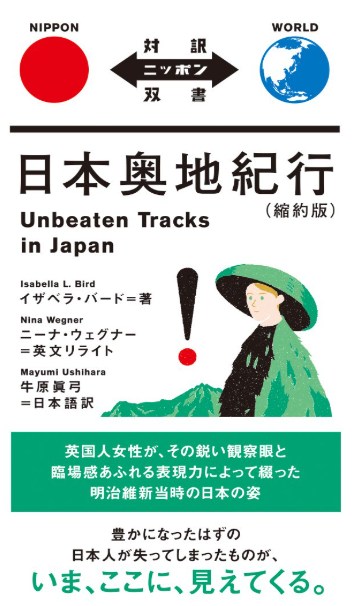

Isabella Lucy Bird, Traveler (arrived 1878)

“In Japan, even the way food is prepared is clean,” she wrote. “Even if the clothing and main houses of the lower classes are dirty, the methods of cooking and serving food are extremely hygienic.”

Her book Unbeaten Tracks in Japan is a classic worth reading. Source: Amazon.com

Isabella L. Bird. Source: In The Footsteps of History

Observations by Missionaries during the Sengoku Period

The Japanese love cleanliness. Buildings, tools, clothing, meals, and work are all kept clean, and it is considered proper etiquette to welcome visitors into a clean space. To Japanese people, dirtiness is absolutely intolerable.

From these accounts, it is clear that cleanliness is an instinctive trait and a natural sensibility of the Japanese. This is also part of their Shinto-influenced sensibility.

One important concept in Shinto is purity. Purification generates mysterious power. In other words, cleanliness is associated with sanctity and strength—a sensibility, aesthetic sense, and value deeply ingrained in Japanese culture.

5-4. Foreigners Without Handkerchiefs

I used to work as a tour guide for foreign visitors.

I took them to Meiji Shrine in Tokyo many times. At the entrance to the shrine’s main hall is a chozusha, a structure where visitors cleanse their hands and mouth before praying. Everyone washes their hands there, but the foreigners did not have handkerchiefs to dry their hands.

Every Japanese person brings a handkerchief and tissue paper.

Ninety-nine percent of them had no handkerchiefs. They would shake their wet hands to flick off the water and then wipe them on their hair or pants. Even the women did not carry handkerchiefs.

In Japan, from a very young age, children are taught to always carry a handkerchief and tissues when going out. Even adult men carry a handkerchief and tissues, and some women carry several handkerchiefs with them. From the perspective of cleanliness-minded Japanese people, Westerners can seem remarkably uncivilized.

6. The Beauty of Shadows and Subtle Light

Japanese people prefer lighting in buildings that is slightly dim or features subtle shadows. They do not favor fully bright illumination. This preference is rooted in a complex mix of cultural, historical, and philosophical factors.

“The Window of Enlightenment” — Source: Kamakura City Tourism Association

6-1. Harmony with Nature

Japan has distinct seasons and strong variations in sunlight and weather. In designing houses and gardens, it is preferred to let in natural light while softening it through shadows in the following ways:

– By using shoji screens or latticework, light reaches the room diffusely rather than directly.

– There is an appreciation for natural shadows, such as sunlight filtering through leaves or reflections on water.

– As a result, spaces that are “not too bright, with gentle shadows” are perceived as comfortable and inviting.

6-2. Shadows as an Aesthetic Sense

Japanese homes make use of natural light. Source: IMURA Wooden Houses.

As noted in the famous Japanese writer Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s book In Praise of Shadows, Japanese culture values “the beauty of shadows.” The reasons include:

– Shadows give depth and character to objects.

– Compared to spaces that are purely white or overly bright, the contrast of light and shadow soothes the mind and creates a sense of taste and nuance.

– This sensibility is shared across tea ceremony, Noh theater, calligraphy, and other arts, where emptiness and darkness foster imagination and serenity.

6-3. Religious and Philosophical Background

– Influence of Buddhist culture: Interiors of temples are never overly bright; quiet spaces for meditation in subdued light are ideal.

– Zen philosophy: Simplicity and space are valued, and gentle light helps calm the mind.

6-4. Climatic and Architectural Reasons

– Japan is humid, and in many regions, sunlight is strong. Intentionally softening light helps maintain comfort.

– In wooden architecture, keeping walls and ceilings moderately bright creates a warm and tranquil room atmosphere.

6-5. Summary

The Japanese preference for “slightly dim light” is not merely a matter of taste. It reflects a combination of:

– A life in harmony with nature

– The aesthetic value of shadows

– Religious and philosophical spirituality

– Practical considerations of climate and architecture

This results in a culture that values the richness, depth, and serenity created by the interplay of light and shadow, rather than fully bright spaces.

I have visited many cities abroad. In numerous buildings, the lighting was extremely bright—so much so that wearing sunglasses was necessary.

At the same time, I visited many dimly lit buildings, but their darkness was not comforting; it did not convey a sense of familiarity. Additionally, spaces that make use of subtle natural light, as is common in Japan, were not often seen.

7. Living in Harmony with Japanese People

Image: Source – NOMAD LIFE

As discussed above, I am not fundamentally opposed to foreigners living in Japan or visiting as tourists.

However, for this to work, I want them to respect the clean living environment that Japanese people have cherished for centuries and to value a spirit of respect toward others. If they cannot do that, I would prefer that they not come to Japan. Japan does not need foreigners to live here or to visit and spend money—it is not a poor country.

Most countries have a proverb like, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” Foreigners should carefully observe how Japanese people live their daily lives and follow suit. This is the only way for foreigners to coexist with Japanese people in Japan. Apart from food habits, they should temporarily forget the lifestyle practices they have followed in their own countries.

Then, they can enjoy the beauty of Japan’s four seasons, the taste of fresh agricultural and seafood products, the charm of traditional events, and peaceful interactions with friendly Japanese people. (The End)