I often hear tourists say that Japanese cities, towns, villages, roads, public squares, trains, bullet trains, etc. are very clean and beautiful. We are also asked why this is so.

Here, I will explain other similar questions from foreign visitors to Japan. I hope that this will help foreign visitors understand Japan better.

I am an English-speaking tour guide certified by the Japanese government tourist bureau for foreigners visiting Japan. I am a Japanese who was born and lives in Japan. For us, Japanese, such things are quite natural. Our life is not a special life, but a normal life.

【contents】

- “In Japan, there is no litter on the streets. It is unbelievable!”

- “The toilets in Japanese homes are wonderful. “

- “Japanese people always wait in line quietly.”

- “We don’t see graffiti on walls in Japan.”

- “In Japan, we only see a few police cars.”

- “I was surprised that we take off our shoes at every temple in Kyoto.”

- “Do all Japanese people carry a handkerchief and tissue paper?”

- Japanese Rational Wisdom for Household Waste Disposal

- “In Japan, students clean classrooms and toilets”

- Cleanliness awareness at community events

- Observation of foreigners visiting Japan in the Bakumatsu period

- Japanese clean the table after eating.

- ”Japanese river water is so clear and we can see the bottom of the river.”

- The root of Japanese people’s love of cleanliness is “Bushido” and “Shinto”

“In Japan, there is no litter on the streets. It is unbelievable!”

Indeed, when I look back on my walks in foreign cities, I saw trash everywhere. In Japan, there is almost no trash on the streets.

Indeed, when I look back on my walks in foreign cities, I saw trash everywhere. In Japan, there is almost no trash on the streets.

Until about 30 years ago, there were trash cans on the streets, at railroad stations, and in large commercial facilities. However, at that time, there was a series of bombings of trash cans installed in public spaces by leftists, so the trash cans were removed.

After that, when we went out and generated garbage, we began to take it back to our homes or to the companies where we worked to dispose of it.

When I guided a tour group, a foreign tourist asked me where he should throw away his beverage bottle.

“The used plastic bottles are either thrown into the trash cans near the beverage vending machines or taken back to the hotel or home for disposal. If you are lucky enough to come across a trash can on the way, you can throw it there. Until then, you carry them with you. This is quite normal for Japanese people.”

We, the Japanese traditionally have valued cleanliness and have long been aware of the value of the environment and natural resources.

From an early age, Japanese people are taught at home and school how to not waste garbage. No one thinks of throwing candy, chewing gum, cigarette wrappers, etc., anywhere because there are no trash cans nearby. If there is no trash can nearby, they take them to their hotel or home and dispose of them.

Smokers are not allowed to smoke outside except in areas where smoking is permitted and ashtrays are provided. Smoking is prohibited in company offices, commercial facilities, and transportation facilities.

But there are clean booths set up for smokers in the streets of Japan.

When going out, walk around with a small plastic bag to temporarily store small garbage.

Japanese people think that people who throw garbage on the streets are bad people, and they do not want to be seen as such by others, so they do not throw garbage on the streets.

“The toilets in Japanese homes are wonderful. “

The first electronic toilet seat (commonly known as a “washlet”) was introduced in Japan in 1980. At first, they could only be cleaned with hot water at the push of a button.

Nowadays, the penetration rate in households across Japan is 80.3% (in 2021. All urban corporate offices, hotels, and large commercial facilities have adopted this system.

Some models automatically raise the toilet lid when approaching the toilet bowl. When finished, the toilet is automatically flushed and the lid automatically closes.

The temperature and intensity of the hot water can be adjusted. Some models can dry the part with warm air.

Once upon a time, the TV commercials for this electronic toilet seat looked like this. Red paint is applied to the back of the hand. To clean it, do you wipe it with tissue paper or wash it with hot water? The result is obvious.

Also, Japanese people do not like to leave any smell thereafter using the toilet. This is a peculiar Japanese sensibility of not wanting to give the next person a lousy feeling. Thus, Japanese people have always had the habit of taking care not to cause inconvenience to others around them or to the next person. Every restroom has deodorizers and air freshener sprays. If you go to a drugstore, you will find many kinds of deodorizers and air fresheners with various flower scents.

“Japanese people always wait in line quietly.”

The Japanese have a habit of thinking and acting in an orderly fashion at all times.

The Japanese have a habit of thinking and acting in an orderly fashion at all times.

It is normal to wait in line at popular ramen stores, sweet stores, and popular events, not to mention buying a train ticket. Employees of the store or event staff may instruct people to wait in line. When the line is long, a placard is prepared to say “This is the last” so that later arrivals can easily see. People who cross the line are very much disliked by others. Japanese people always try to not do things that others do not like, so they do not enter sideways.

In the morning, during rush hour, when the trains and platforms are very crowded, the people getting off the trains have the highest priority, and the people getting on the trains get on after all the people getting off. People boarding the next train wait in line for the next waiting zone. This is because it is more efficient to get on and off the train.

I remember one time when I was talking with a subway station staff in Osaka during a guided tour of the city. Suddenly, a beautifully dressed young woman interrupted me and started asking station staff questions. From my point of view as a Japanese, the woman was outrageously rude. I strongly told her in English to get in line at the end of the line behind me. The woman was Chinese. I knew well from TV programs that Chinese people do not form lines. This kind of attitude is often seen at ticket booths in museums, and it is very much disliked by the Japanese.

There is a saying, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do. Regardless of how you do things in your own country, I hope you will do as the Japanese do when you come to Japan.

Japanese people understand very well that in any event hall or crowded train station, waiting in line will make paperwork and work more efficient and the whole thing will go better.

“We don’t see graffiti on walls in Japan.”

Japanese people generally do not write graffiti on outdoor walls. Of course, there are some who do, but they are few and far between.

At large building construction sites, the construction company will post pictures of beautiful forests on the walls of the site’s enclosure to soothe the public’s eyes.

Sometimes, they post many pictures drawn by pupils of nearby elementary schools.

In any case, every Japanese person has a desire to keep the city clean.

“In Japan, we only see a few police cars.”

When I travel abroad, I see many police cars a day, their sirens blaring, speeding through the streets. In Japan, on the other hand, we don’t see many police cars.

According to recent data from NUMBEO, Venezuela has the highest crime index of 142 countries in the world at 82.6, while Japan ranks 135th at 23.1. In other words, Japan is a comfortable country to live in with a low crime rate in the world. It is so safe that women can walk alone in the streets late at night.

According to a 2012 WHO survey, Japan ranks 193rd out of 194 countries in terms of the number of murders per 100,000 people, with a rate of 0.4. Because of this low crime rate, police cars are rarely seen in Japan.

However, one should never let one’s guard down. You can never be too careful in preventing crime while traveling in Japan.

“I was surprised that we take off our shoes at every temple in Kyoto.”

In Japanese houses, we usually take off our shoes at the entrance and wear socks or barefoot indoors. The same is true in Western-style buildings in Japan, but slippers are sometimes used indoors. Whether the house is a traditional Japanese-style building or a new Western-style building, it is normal to take off our shoes at the entrance. We Japanese always keep our houses clean.

According to what I have heard from foreigners visiting Japan, there are floor grates or floor mats at the entrances of Japanese houses, making it difficult to know where to take off their shoes. Basically, you are not allowed to step on the floor mats or floor grates at the entrance. Please take off your shoes before walking on the floor higher than the soles of your shoes.

In traditional Japanese-style buildings, the floor consists of tatami mats. We Japanese sit on tatami, either directly or with a zabuton(cushion), to relax, drink tea, or eat. Sometimes we lie down and relax. Infants sometimes crawl around on the tatami. At night, we sleep on futons(thick bed quilts and mattresses) laid out on the tatami mats. Therefore, the floor in the home is always clean, just like a Western bed anywhere. Anyway, we must always take off our shoes at the entrance to keep clean inside the house.

In both traditional Japanese-style buildings and newer Western-style buildings, toilets have slippers that are used only for toilets. We use the slippers only in the restroom. Do not wear them inside the room.

Thus, in traditional Japanese-style buildings, as well as in newer Western-style buildings, the interior is kept very clean. Therefore, it is outrageous for Japanese people to enter a room without taking off their shoes after walking somewhere dirty outside.

The same is true of temples and shrines in tourist areas, where the rooms are kept very clean, so even if it is a hassle, you have to take off your shoes to enter the building of the temple or shrine.

Company offices are now completely Western-style, so there is no need to take off your shoes, either in your own office or that of your clients.

In elementary, junior high, and high schools, students take off their outdoor shoes and change into indoor shoes when entering the school building. The rooms are cleaned daily by the students.

“Do all Japanese people carry a handkerchief and tissue paper?”

I would like to share my experience as a tourist guide. I guided about 10 European tourists to the Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo. Before offering prayers, we purified our hands and rinsed our mouths at the temizuya, hand- and mouth-watering booth. Japanese people wipe their wet hands and mouths with a handkerchief. This is a very natural behavior. However, the tourists waved their wet hands to let the water droplets fly away and wiped the rest with their hair or jeans.

Later, I guided other groups and families (all from Europe, the U.S., and Australia) around, but most of the tourists did not have handkerchiefs. Why didn’t they have them? What do they do when they go to the bathroom?

We, the Japanese people have the tendency of being neat and tidy, so a handkerchief and portable tissue paper are a must item when outing. When we were children, mothers always checked them when they went out.

Every Japanese person, young and old, male and female, has a handkerchief and portable tissue paper. Naturally, we bring a new one every morning. If we forget, we buy them immediately at a convenience store or station kiosk.

We do not bring handkerchiefs that we used the previous day. Some foreigners are said to sniff their snot with a handkerchief and walk around with the handkerchief in their pocket. It is unbelievable for us. We use tissue paper when we sniff. We never use tissue paper again.

Japanese Rational Wisdom for Household Waste Disposal

Foreign visitors to Japan were surprised by the following

In the morning, sales clerks in the shopping arcade sweep clean in front of their shops before opening. Shop doors and show windows are also wiped clean. Apartment and condominium managers and landlords do the same.

Employees of small companies also clean up the outside of their offices and buildings before the start of the workday. Some do it after work.

This is because they want customers to have a good image of their company. Whether it is a ship or a company, it is not enough to just sell products or increase sales; it is important to generate a good image of the shop or company among customers.

Another factor is respect for their own workplace. They have respect for the workplace where they can work and are cared for. A common sense of beautification and respect for the workplace is what keeps it clean.

In most supermarkets in Japan, store clerks bow to the sales floor when they come out on the sales floor and when they leave the sales floor. This is a sign of respect for their workplace and for their customers.

Athletes in judo, sumo, soccer, marathon running, and many other sports also bow to the field of play after a match. This is an expression of gratitude and respect for the playing field.

Once upon a time, when Japan was still a peaceful country, there was not so much household garbage. vegetables, leftovers, and other food scraps could be buried in the garden. Combustible garbage could be incinerated in the yard.

However, as we nowadays live in an age of mass consumption, unwanted bottles and cans containing foodstuffs and seasonings are now produced, and plastic packaging materials containing vegetables and meat are now produced. Households are no longer able to dispose of these wastes.

So local governments began to collect household garbage in special trucks and transport it to the appropriate disposal sites. However, since it is not possible to incinerate all garbage at the same time, it is collected by sorting it by type.

For example, in the municipality where I live, the garbage to be collected on each day of the week is determined as follows.

- Wednesday and Saturday => Combustible garbage (paper waste, leftover food, raw vegetable garbage, etc.)

- Tuesday => Plastic bottles, plastic, vinyl, etc.

- Thursday ⇒ Old newspapers, old magazines,

- Friday ⇒ old clothes, cloth-related

Collection of the above is free of charge. You can take this garbage to the designated place (within about 30 meters of your house) by yourself. After the collection is finished, residents take turns cleaning the area.

Apart from these daily garbage, furniture, TVs, bicycles, and other items that are no longer needed will be collected for a fee. If you transport them to the disposal site by yourself, it will be cheaper.

Some municipalities have more than 10 different types of sorting.

Even at drive-ins on highways, garbage cans are usually provided for four types of garbage: burnable garbage, non-burnable garbage, cans, and bottles, but basically, people are encouraged to take their garbage home.

As described above, there are various rules for garbage separation in Japan. This is how we have always been aware of garbage separation since we were small children. No one thinks of “littering.” Japanese people are a race of people who follow the rules correctly. We think it is shameful to throw garbage carelessly.

“In Japan, students clean classrooms and toilets”

In Japan, students in public elementary, junior high, and high schools clean classrooms, toilets, and schoolyards by themselves. They also need to clean corridors, and other rooms such as the music room, gym, and science room. Cleaning is a part of their daily routine which usually starts soon after the lunch break or at the end of the day.

At Japanese schools, students are responsible for keeping their classrooms clean.

At many schools, each classroom has a locker for cleaning tools such as brooms, buckets, cleaning rags, dustpans, and brushes.

The cleaning committee is appointed from the class and evaluates the results of the cleaning on a scale of, say 5. The cleaning group that does not receive a good evaluation cleans the area until it receives the highest score.

This is an expression of our sense of beauty and respect for the place where we study and keep it clean.

Some private schools hire outside cleaners to do the cleaning.

In this way, Japanese students naturally learn the importance of cleanliness from a young age.

Cleanliness awareness at community events

The Japanese sense of beauty is on full display at events where people from all walks of life enjoy themselves together, such as cherry blossom viewing in the spring, Bon Odori dancing in the summer, children’s baseball games, soccer games, and so on.

After the event is over, anyone and everyone picks up trash and collects it in a designated area. They also collect trash left behind by drunken revelers. After the trash is picked up, the area is swept clean.

The aesthetic sense of returning something you used to be cleaner than when you received is ingrained in each Japanese individual as a sense of morality.

This is something that the children who come to the events with us learn firsthand.

Observation of foreigners visiting Japan in the Bakumatsu period

Bakumatsu refers to the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate (Edo period). Generally, it is the period from the opening of the country with the conclusion of the Treaty of Amity between Japan and the United States in 1854 to the abolition of feudal domains by the Meiji government in 1871.

Foreigners who came to Japan at the end of the Edo period noted that the Japanese were a clean people as follows;

British Minister Sir Rutherford Alcock (came to Japan in 1859)

”In general, the Japanese are clean people and wash themselves frequently without fear of being seen. They live in well-ventilated houses. They live in airy houses, which face a wide, airy street. They are not allowed to leave any unpleasant items or baggage on the street. The Japanese have a great advantage over other Oriental peoples when it comes to cleanliness, especially over the Chinese.”

Danish naval officer Edouard Suenson (who came to Japan in 1866 and had valuable experiences in the vicinity of French Minister Léon Roche)

”The Japanese love cleanliness far more than Europeans. Not only in their houses but also in their character in general. A day is not complete without going to a public bath after work. They spend hours in public baths, bathing, washing their underwear, and chatting.”

German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann (came to Japan in 1865)

”There is no disputing that the Japanese are the cleanest people in the world. Even the poorest person goes to a public bath at least once a day in every town.”

For the Japanese, the custom of foreigners was felt to be very filthy. That is biting one’s nose with a handkerchief. The Japanese use chirigami (like tissue paper);

Edouard Suenson said, “Westerners carry a filthy handkerchief in their pocket all day” and the Japanese just don’t get it,” and Schliemann wrote, “The Japanese are horrified that we carry the same handkerchief for days on end.

U.S. Consul General Townsend Harris (arrived in Japan in 1856)

Harris lived in Shimoda, Shizuoka Prefecture, where the U.S. Consulate was located. He noted that the Japanese were clean, even though they were poor.

“The Japanese are clean in spite of their poverty,” Harris said, “and I see not a trace of the filthiness which always accompanies poverty in all countries of the world. Their houses are as clean as they need to be.

Traveler Isabella Lucy Bird (arrived in Japan in 1878)

She said, “The Japanese way of cooking is clean, too.” No matter how dirty the clothing and main house of the poor may be, the way they cook and the way they serve their food is extremely clean.”

A missionary who visited Japan during the Warring States period(1467-1615).

“The Japanese love cleanliness. They keep their buildings, tools, clothes, food, and work all clean, and it is polite to welcome visitors to a clean place. For the Japanese, uncleanliness is absolutely intolerable.”

The above observations by foreigners indicate that the love of cleanliness is a natural instinct and sensitivity of our Japanese. This is also the Shinto sense of the Japanese.

Japanese clean the table after eating.

After a meal, the Japanese table is very clean. Leftovers are collected in one place, and dirty tables are wiped clean. This is a statement of attitude that they enjoyed their meal and did not make the dishes and table too dirty.

They do not use dishes and tables and leave them soiled but finish the meal as clean as before. This is the pride of the Japanese people.

The Japanese always have a sense of not causing trouble or discomfort to others. When eating a meal, there are certain eating manners, which are basically to avoid causing discomfort to those present. There is also a strict etiquette for the use of chopsticks. These manners are not merely good manners but are a Japanese aesthetic.

”Japanese river water is so clear and we can see the bottom of the river.”

Indeed, Japanese river water is clear and clean no matter where you look.

However, this is not because Japanese people like cleanliness, as I have explained so far, ha, ha, ha.

The following is a possible reason for the near-transparency of river water in Japan.

That is because 70% of Japan’s land area is forest, and there are many trees.

The forests where trees grow are covered with rich soil. The soil is home to many microorganisms. These microorganisms purify rainfall and dirty water.

Rain that falls from the sky soaks into the soil through the trees, passes through the fallen leaves on the soil, passes through the soil decomposed by the microorganisms, and reaches the ground.

The water becomes even cleaner as it flows between the rocks underground.

In addition, as the river flows through nature, the pollution in the river is broken down and cleaned by living organisms in the river (bacteria, humiva, and other small microorganisms that are invisible to the eye). This is called self-cleansing.

Thus, the water in Japanese rivers is clean because it comes through rich forests, and appears almost transparent in color.

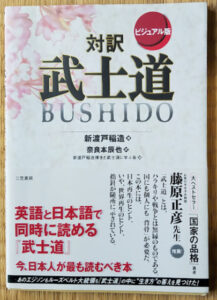

The root of Japanese people’s love of cleanliness is “Bushido” and “Shinto”

The above is an explanation of the cleanliness of our Japanese people that surprises foreign visitors to Japan. While this may come as a surprise to foreigners, for us Japanese, keeping our surroundings clean is not a matter of special effort, but rather a natural outgrowth of our own behavior.

In Buddhism and Japanese Shintoism, cleanliness has historically been regarded as an important part of religious practice.

The Japanese educator and thinker Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933) wrote a book in English titled ”Bushido, The Soule of Japan”(1899). This book explains the spirit of Bushido, which is at the core of our Japanese sense of morality. In it, he explains the “shame” of the samurai.

The Japanese educator and thinker Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933) wrote a book in English titled ”Bushido, The Soule of Japan”(1899). This book explains the spirit of Bushido, which is at the core of our Japanese sense of morality. In it, he explains the “shame” of the samurai.

It explains that the “shame” of the samurai is the internal sense of humiliation and dishonor that arises when one does not behave in a manner that is expected of one’s social position, role, and family name.

The reason why we Japanese people today do not throw trash into the streets is that we have inherited this spirit of shame from Bushido. It is “shameful” and “dishonorable” to throw garbage into the street or to leave our own used articles soiled.

From the perspective of Shinto, the religion of Japan, the Japanese love of cleanliness can be explained as follows.

Shinto is the totality of the lifestyle and values of the Japanese people that has become a religion. Therefore, there are no doctrines, no precepts, and no standards of right and wrong. What is important is purity. When we purify(kiyomeru, a verb in Japanese), a mysterious power arises from it. In other words, we feel holiness and power in cleanliness(kiyome, a noun in Japanese), this is the sensitivity, sense, and values that the Japanese have.

This culture of “Kiyome” is a culture that believes that by purifying things, places, and people’s hearts, we can increase their sacredness and beauty.

Specifically, when we, the Japanese visit shrines and temples, we purify our hands and mouths at a temizuya. On special occasions such as New Year’s and Obon, there is also the custom of cleaning and purifying houses and cemeteries.

One of the fundamental beliefs of Shintoism is that impurity or uncleanliness, which is called Kegare in Japanese, should be removed before entering the sacred grounds of Shinto shrines.

In addition, Zen meditation at Zen temples and meditative activities such as tea ceremonies are also considered important in the culture of purification for the purpose of purifying the mind.

In this way, we, the Japanese people believe it is important to pay respect to nature and sacred objects in daily life and to purify the body and mind through purification.

This Shinto aesthetic sense is at the root of the Japanese mentality as a whole and is probably reflected in their love of cleanliness in their daily lives.

It can be said that the above “Bushido” and “Shinto” backgrounds are the elements that make Japanese people keep cleanliness in mind in various aspects of their lives.